Your Trusted Partner in Building Success

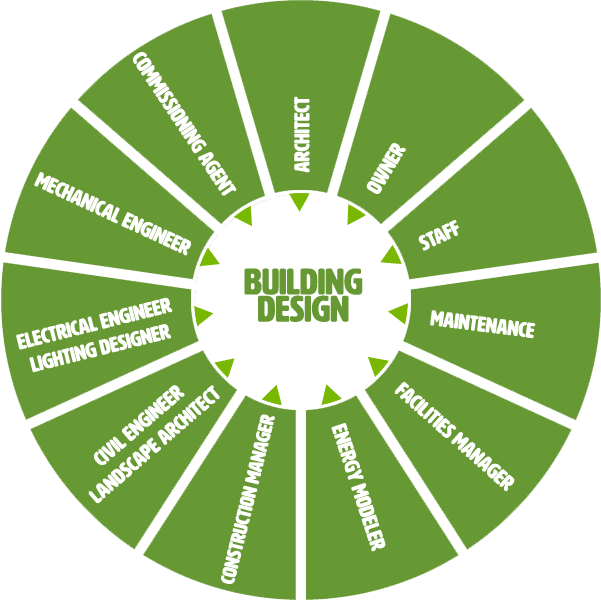

As an architect, during the design process the project is envisioned to become the best building it can be, the best building it wants to be. Nothing is purer than the concept of the building unadulterated by worldly pressures that, will certainly come to bare. That is why I am very stingy with compromises early on the design process, the earlier in the process the stingier I am. That is because there will always be compromises and trade-offs. The longer the architect can hold those off, the better the overall quality and value of the final building. The key is keeping the designer’s eye on the prize—the final built project. How does the building function? Does it work well? Is the building of value? Is it worth the overall cost? Is it safe, healthy and comfortable? Is it aesthetically pleasing? Is it architecture?

The Evolution of Construction: From Master Builder to Today’s Specialists

Over the centuries, the architect was also commissioned to build the building. It was a natural selection for the owner and the logical choice to bring the building from design out of the ground. The design process and its intent are held in the architect’s vision and more effectively brought to life by the architect. This is where the term “Master Builder” came into use regarding the architect. To me, the holy grail is in the quality of the built project. Professionally it’s all I care about. In our current business model this process has dissolved. Architects design and builders build—the thinker and the doer, with no allowance for the other.

There are two main methods for product delivery in the design and construction trade. The first is called “Design, Bid, Build.” Ths is the industry standard for the vast majority of construction projects. The second is Construction Management (CM). The following is a description of each and how our firm approaches the building process.

Concept

Historically, architects played the role of “Master Builder,” overseeing both design and construction. This ensured a clear vision translated into a quality built project.

Shifting Landscape

Our Philosophy

Design-Bid-Build: Understanding the Traditional Method

In the Design Bid Build process, the architect interacts with the client, determining wants and needs. Those requirements are implemented and result in a bid package of contract documents, a set of drawings and written specifications. The general contractor (GC) receives the contract documents, distributes them to the subcontractors, receives their prices, and adds the their cost of project supervision, overhead and profit. Then they provide the owner with a single price the general contractor must live or die by. Typically, the lowest bid wins.

Some general contractors have some construction personnel on direct payroll, usually carpentry skilled, but even those will subcontract for major framing and sheathing. The industry standard is that contractors add 30% to their estimated costs, but there is no way of knowing the actual numbers regardless of what paperwork the general contractor provides.

If all bidders are over budget, it’s back to the drawing board for redesign. The architect typically bills additional fees for the redesign. This process is opaque to both the owner and the architect. A general contractor may be asked and may provide cost breakdowns of the price but there is no reassurance that these numbers actually represent real costs. They are merely a means for negotiation of payments and extras.

Ah extras! An extra is something that is not on or not clear in the contract documents, not priced by the contractor and additional to the general contractor’s price, and always a point of contention. Extras happen most frequently in renovations. The quandary to the architect and the owner is, what if the cost of the extra is high or perceived as high? The owner considers it an error or omission by the architect, and that the contractor is looking to increase their profit. What to do? Bring in another contractor to competitively bid the extra work to check the one that is on the job? Bite the bullet and pay the contractor what they ask? Sue the architect? Regardless, if this work is required to complete the project, it’s part of the project cost.

The Design Bid Build system sets up an adversarial relationship between the architect and the general contractor, all at the owners cost and to the detriment to the quality of the final product. It behooves the contractor to cut and scrape costs to their minimum to increase profits which are unknown to the owner and architect.

The Process

Potential Challenges - Limited Collaboration

Potential Challenges - Opaque Pricing

Potential Challenges - Change Order Issues

Potential Challenges - Focus on Cost, Not Quality

Our Alternative

Construction Management: Building Together for Better Outcomes

The main difference between the Construction Management model and the Design Bid Build model is that the sub-contractors such as carpenters, plumbers and electricians work and are contracted directly to the owner. Their costs are directly known to the owner. The construction manager is involved in the project early and can provide preliminary pricing during the design process to ensure the project construction budget and schedule are on track. The construction manager is paid to provide this service and then is paid to supervise the process. The fee structure is based hourly on the construction managers time which is pre-estimated in the initial proposal, and or by a percentage of subcontracts. As all contracts are made directly with the owner, the costs are clear.

Another benefit of the Construction Management Model is that the owner can directly purchase large-ticket items like windows, kitchen cabinets and even HVAC equipment. This avoids contractor mark-ups. All this with the guidance and interface of the construction manager, which helps assure complicated deliveries are what the contractor expects to receive.

The time and cost of the construction manager to coordinate both materials and services may cost the same as what a general contractor may have in the price, but the level of control is another value added feature to the CM model. More often than not, the Construction Management process results in lower costs that are passed on to the owner as opposed to disappearing in the general contractors spreadsheet. Clearly the Construction Management model stands the best chance of successful delivery of the architect’s vision.

Owners may shy away from hiring a construction person early in the project and traditionally have held off until the competitive bidding phase so that they can pit general contractors against each other to get the best-looking price. In the Construction Management model the competition takes place when subcontractors bid on their specific trades. A construction manager will collect prices from multiple plumbers, electricians, or framers and present each to the owner with track record and vetted information.

At Paul Cataldo Architecture and Planning I prefer to evolve the construction management method of delivery back into the Master Builder role, providing design-build using the construction management model. I’ve found over the years that the things I give up control on fall prey to the value ax at the cost of the owner and the quality of the project.

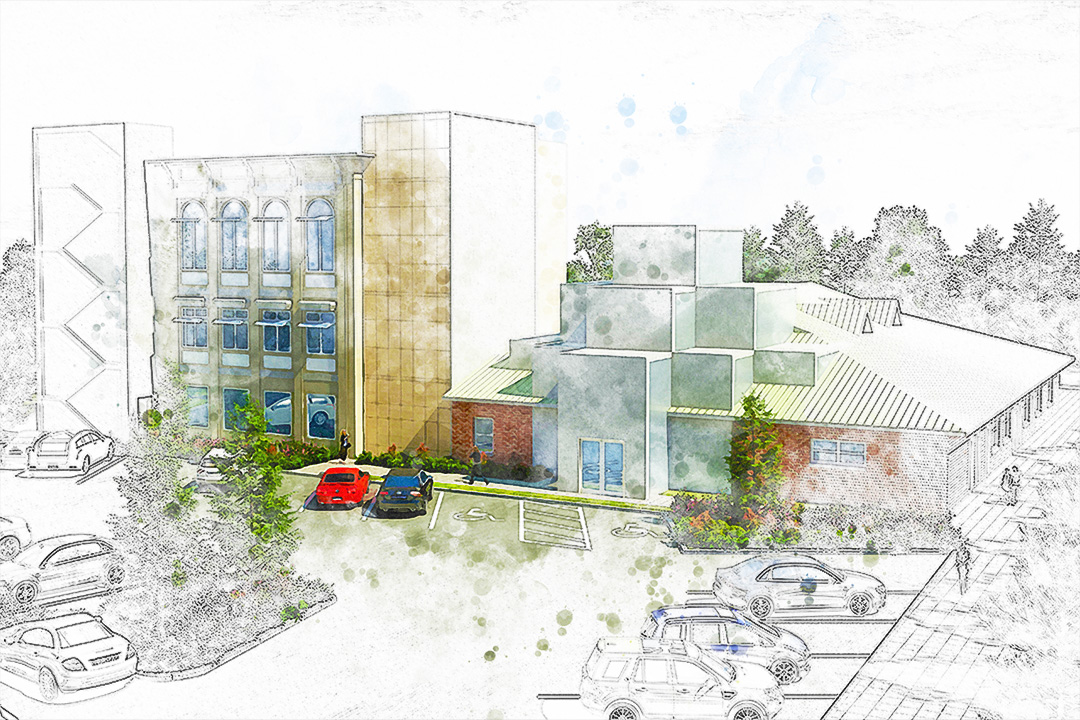

The coordinated pre-determined path through construction requires the team to be assembled from the start: informed, verified, planned, executed. This type of early decision-making using the tools that produce verified information leads to quality decision making—early decisions like the exact selection of the mechanical system, weighing the system’s initial costs against life-time assessment cost. This requires an integrated approach since the mechanical systems are directly integrated with the building envelope, orientation, fenestrations, and many other factors, all computer-modeled so that effective cost analysis can drive the best quality for dollars spent.

Each building is a custom-built first-time machine compiled by off the shelf materials and machines. PCAP, PC is the integrated approach to creating buildings.

Transparency and Control

Early Collaboration

Reduced Markups

Quality through Collaboration

Value-Driven Decision Making

Master Builder Philosophy

Integrated Design: Orchestrating a High-Performing Building

The Master Builder or Integrated Design approach likens the architect to the composer and the conductor. The concept combines the development and the execution, requiring the many moving architectural parts of safety, comfort, enrichment, productivity, and health to be orchestrated into harmonic functionalism.

Short-term savings in the “first cost” (i.e. construction costs) make for a non-efficient and an operationally costly building for the foreseeable future. Many prefer to reduce expenses is this first cost phase, yet construction costs make up less than 10% of the building’s operation cost over the building’s expected lifespan, with the average closer to 6%. Again, the goal is a valued, quality building.

To that end, Paul Catalado Architecture & Planning offers integrated design and construction management to facilitate the type of buildings that are profitable, healthy, and environmentally restorative.

Beyond Minimums

A Collaborative Symphony

Long-Term Value

Profitability, Health & Sustainability

A Spectrum of Sustainable Design Services.

Commercial Green Building

Elevate Your Business with Sustainable Design

Our expertise in commercial green building helps businesses reduce operating costs, improve employee well-being, and achieve sustainability goals. We create high-performing spaces that contribute to a healthier planet and a more productive work environment.

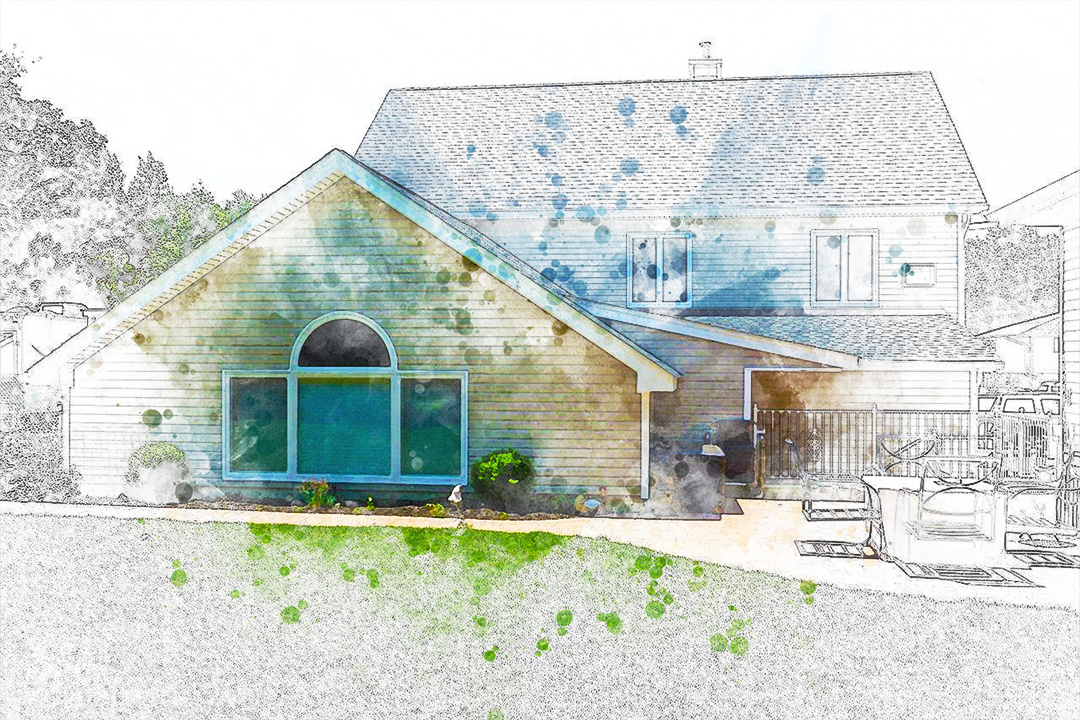

Green Home Design

Build Your Dream Home with a Sustainable Soul

Imagine a comfortable and stylish home that minimizes your environmental impact. We specialize in new residential buildings and green home remodels, incorporating green interior design, sustainable landscape design, and Net Zero Energy building practices.

LEED Certification

Achieve Recognition for Your Green Building Efforts

As a founding member of the Long Island chapter of USGBC, we offer expert guidance on LEED certification. We’ll navigate the process and ensure your building meets the highest sustainability standards, maximizing its environmental and economic benefits.

Sustainable Landscape Design

Our team of landscape architects crafts beautiful and functional outdoor environments that benefit the environment. We incorporate native plants, water-efficient irrigation systems, and sustainable materials to create a space that minimizes water usage and promotes biodiversity.

Net Zero Energy Design

Imagine a home that produces as much energy as it consumes. Net Zero Energy Design minimizes your reliance on the grid and reduces your carbon footprint. We create energy-efficient building envelopes, integrate renewable energy sources like solar panels, and utilize smart home technology to achieve a Net Zero Energy home.

Construction Management

Our experienced construction management team oversees every aspect of your project, ensuring it stays on budget, on schedule, and meets the highest sustainability standards. We provide clear communication, manage subcontractors, and handle all logistical aspects to deliver your green building dream into reality.

Ensure a Smooth Green Building Project with Construction Management >

Our Sustainable Design Team.

Paul Cataldo Architecture & Planning is driven by a team passionate about sustainable design. Explore Paul Cataldo's profile, the leader who ignites this green vision.

Paul Cataldo

Architect

At Paul Cataldo Architecture & Planning PC, an integrated approach to design is the natural process. Mechanical, electrical, and site design is important to the overall quality of the building.